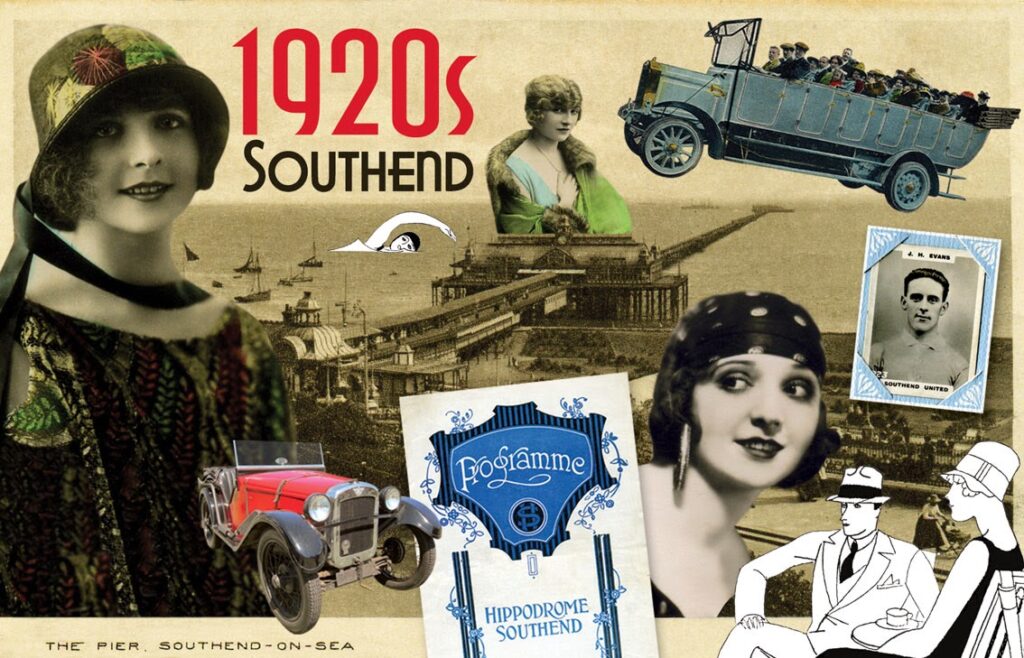

The 1920s was a decade of change. Eager to throw aside the horrors of war, rationing and a devastating Influenza, people enthusiastically embraced new music, clothes, hairstyles and technology. The Roaring Twenties had begun … much of it influenced by the United States, movies and jazz became all the rage. Wealthier ‘Bright Young Things’ with their stylish bobs and daring hemlines took to the clubs and dance halls with gay abandon, while housewives demanding more leisure time, were offered affordable devices like refrigerators, washing machines, electric kettles and Hoovers.

Popular sweet makers, like Cadbury and Fry’s increased their chocolates range, creating the still popular Flake, Fruit & Nut and Crunchie bars, however toffee remained the go-to cheap and cheerful staple.

It was not all “Jeeves and Wooster” for the working classes however. Despite the initial boom after WWI, a lingering financial depression led to massive unemployment with over 2 million jobless across Scotland, Wales and Northern England. Soup kitchens and slums were commonplace and despite a 9-day General Strike in 1926, involving 1.7 million trade unionists, coming out in solidarity with the miners, conditions did not significantly improve for mine workers. Surprisingly, not a lot of violence was recorded – in fact, on May 8th, the fourth day of the strike, a football match took place in Plymouth between police officers and strikers . . . the strikers won 2-0.

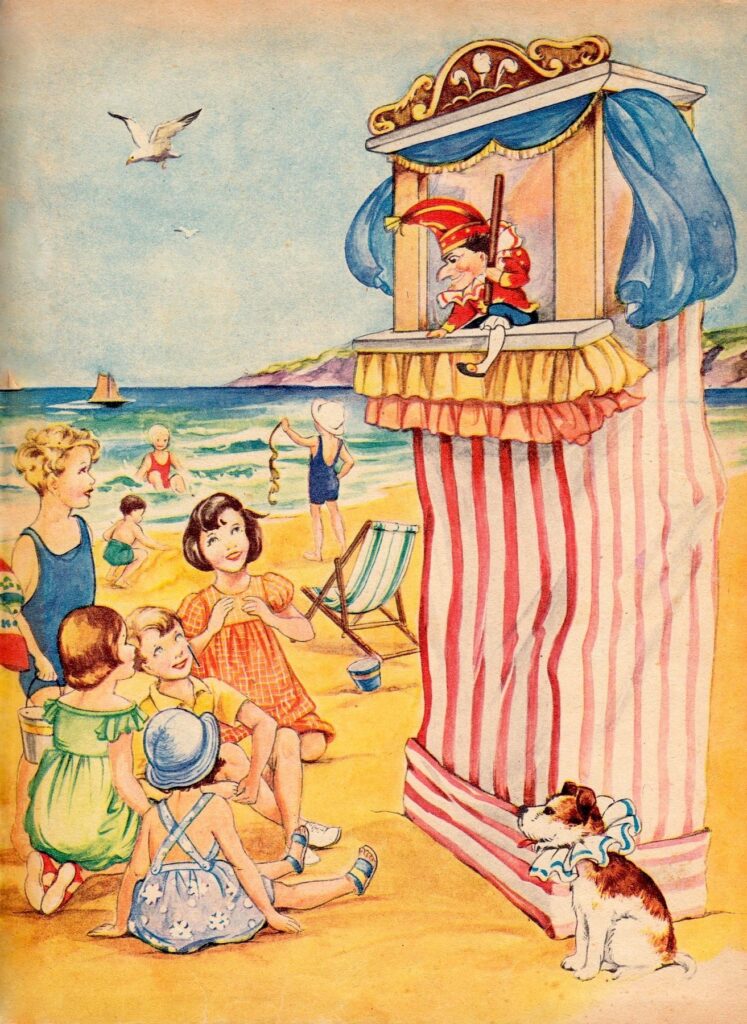

Rambling and cycling became popular pastimes, as did rail travel. Families weighed down with buckets, spades and picnic hampers would make day trips to beaches and towns along the coast — places like Blackpool, Whitby, Margate, Clacton, Brighton and Bognor. Enterprising locals soon saw opportunities for deckchair rentals and beach hut use; winkle, whelk and ice cream sellers discovered new audiences, and entertainment for children became popular as Punch and Judy shows and Donkey Rides sprang up along the beaches. The amalgamation of two war-time airfields at Croydon became London’s first international airport, although initial air travel was limited to a few European countries. Transatlantic journeys, like those between Southampton and New York, still required five days onboard a steamship.

The blossoming motor age completely transformed everyday life. At the start of 1920, there were around 300,000 motorized vehicles on British roads, however this number virtually doubled by the end of the decade. Journeys were perilous, though. Slower traffic, like horse-drawn carts, carriages, trams and bicycles vied for space with these new-fangled upstarts. It was quite evident that no-one followed whatever ‘rules of the road’ applied at the time. Pedestrians, who still held the ‘right to saunter’ merely added to the melee, and by 1929 mishaps between people and cars had resulted in 6,000 deaths and more than 220,000 injuries. The average Bobby was ill-equipped for handling the congestion, volume and variety of traffic on streets that were never intended for such purpose. Desperate city councils experimented with ‘automated policemen’ (traffic lights) and a somewhat generalized Highway Code which restricted motorists to the roads and pedestrians to the pavements, with designated crossing places. Video of London in 1924 – remastered by NASS on Youtube with colour and sound. Quite amazing.

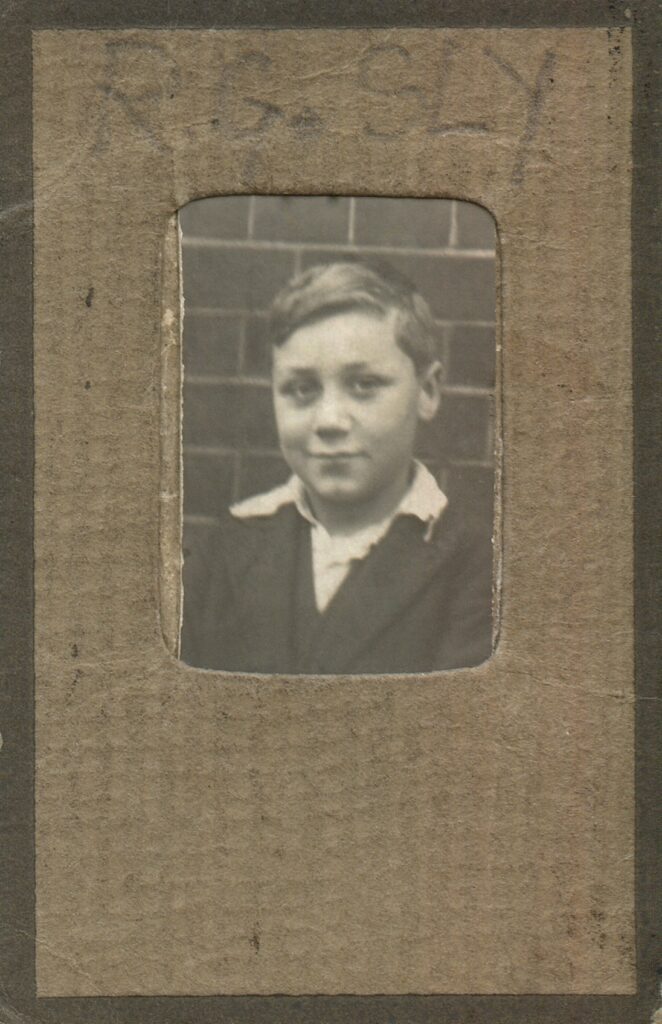

It was into this world, around dinner time, on February 24th, 1920 that Ronald Gordon Sly made his appearance at 178 Shoringham Avenue, Manor Park in East London – the home of his grandparents. A healthy, bouncing 9 lbs 1 oz. Hardly an event of great consequence to anyone other than his parents Albert and Kate and a relative or two, but possibly of some significance to the people now reading this account. It had been a cool, sunny day – more seasonal than the previous week when temperatures had risen to a balmy 59°F (15C). Albert, a journeyman Motor Engineer had stopped by after work to visit with his brother-in-law Will and wife Maggie in Hammersmith, so was blissfully unaware of the good news until returning home around 8 that evening – a fact that Kate was always careful to mention

One of RG’s first outings was by pram to the Post Office and general store. As was commonplace at the time, babies were left asleep in their prams outside, while mums collected their shopping. Laden with purchases, and completely forgetting pram and sleeping baby, Kate hopped aboard a conveniently passing bus back home. “Where’s the Baby?” exclaimed an anxious mother-in-law as she entered the kitchen. A hurried return trip safely retrieved both pram and infant.

Kate’s sister-in-law Maggie recalled another incident when RG was sitting in his pram dressed in the fashion of the day – a bonnet and long frock-like garment. Prams were very well sprung in those days, so when a passing dog took a sudden interest and pounced on the pram’s handle to get a better look, infant Ron was catapulted through the air like Halley’s comet with clothes streaming out behind. (Story courtesy of cousin Bill Reynolds).

Baptism took place two months later on the 18th April at St. James’ Church on Tower Road, Clacton-on-Sea … not far from the famous pier and pavilion. Inside St. James short video (26 sec)

Great Aunt Dora (sister to RG’s grandmother Sarah) had a large house in Finsbury Park North London (63 Marcellus Road – no longer there but very close to Hornby and Mayton Roads). It was a favourite spot for family gatherings and celebrations. Although regular radio broadcasts were just becoming popular, not many homes had a wireless, so entertainment was usually of the home-made kind. Songs around the piano, charades or reciting well-known poems or comical ditties. At one such gathering, little RG pestered and whined all evening that he wanted to sing “Little Honey Bee”. Finally, his exasperated mother plonked him on the kitchen table and said, “Well sing Little Honey Bee, then!” “Don’t want to”, was the petulant reply!

Several other childhood events were linked to Aunt Dora’s house – the gleeful poking of an old pig with a rusted umbrella, apparently just to hear it grunt; trimming the cat’s whiskers because ‘they should all be the same length’; and mysteriously ending up at the bottom of deep garden hole with just the faintest of voices wafting out.

Christmas 1927 brought gale force winds and blizzards to all of southern England, and food had to be brought in on sledges or dropped by planes. London suffered the heaviest snowfall ever recorded, with snowdrifts up to 20 feet. Everything ground to a halt. With temperatures dropping to minus 8oF, a critical shortage of coal and no central heating, it was dangerously cold for most people … especially as many houses only had outside toilets. These conditions lasted into the new year when a sudden wind change and dramatic thaw caused the Thames to burst its banks and devastate the low-lying areas of the city. Fifteen percent of London was built along the flood plane, with a hidden network of underground rivers right below their feet. Entire streets were submerged and 14 people died — many in their own basements.

As he got older, R.G. and his mates were always up to something. They had in their possession several squares of flat metal which when dropped together onto a cement pavement created a noise remarkably like a plate glass window shattering. These they employed very successfully outside of storefronts — hiding before the irate shopkeepers rushed out to see who had just broken their window.

Another favourite was to tie several dustbin lids to people’s front doors, ring the bell and hide – watching with glee as owners cursed and struggled to open their doors. Autumn brought scrumping at Bisants’ orchard off Lonsdale Road in Barnes. According to best mate (and cousin) Bill Reynolds “after having our share of fruit we stood outside enjoying the apples when the watchman appeared on the scene and started shouting at us. We all threw the remaining apples at him and ran like blazes for safety”.

Christmas was the time for “Fear Not” cakes, when for 3d one could buy a bag full of day-old cakes from the local bakery with which to sustain oneself while caroling. Some were perhaps a little older and crumblier, and these would be carefully saved for the second verse of “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks”. Great emphasis on the words “Fffear not said he with mighty dread” would leave a satisfying snowstorm of crumbs on someone’s doorstep. It’s quite possible, of course, that the entire first verse had been re-worded thusly:

While Shepherds washed their socks by night

All seated ‘round the tub

A bar of Fairy snow came down

And they began to scrub.

As with all young boys RG was outgrowing his clothes at an alarming rate so Kate in a moment of desperation asked her mother-in-law Sarah (a skilled tailoress) to convert an old pair of his father’s checkered plus fours into some serviceable trousers. R.G. loathed them on sight, vowing never to wear them. One Saturday, however, with nothing else to wear he donned the dreaded garment and went off to play with his mates near Hammersmith bridge. After swimming, they got dressed and sat on one of the huge barges moored there, having previously used it as a diving off point. It was a scorching day in June and the deck tar had turned to the consistency of glue. RG was stuck fast. Not deterred, his mates assisted by giving him a mighty heave, successfully leaving the seat of his trousers behind and ensuring he never had to wear them again.

Once, as his mother and sisters were walking across the bridge, a familiar voice floated up from the Thames below. Peering cautiously over the railing, they spotted young RG treading water and waving merrily to them, as barges and river craft passed by. This short video (no sound) shows a little of the Thames river traffic. At around the one minute mark is a section that would have been more familiar to a young RG.

His fascination of all things London probably began with his first school — St. Paul’s, Hammersmith – attended by his mother Kate and several of her her siblings. Built on its original site in 1509 by John Colet, eldest son of Sir Henry Colet, and only surviving child of 21 siblings. As a celibate priest with no family of his own and a considerable inheritance burning a hole in his pocket, John elected to provide education for 153 children of “all nacions [sic] and countries indifferently”. Long associated with the second Miraculous Draught of Fishes (St. John’s Gospel), 153 refers to the number of fish gathered from Galilee, and no doubt led to the adoption of a silver fish as school’s emblem.

Boy scholars (girls were not admitted until 1904) were not required to pay school fees, however they did need to be literate, and able to provide their own candles, which apparently at the time were quite expensive. In spite of, or perhaps because of his chosen profession, Colet had a healthy distrust of Church intervention in school matters and handed over financial management to the leading livery company in London. With contemporaries such as Sir Thomas More and Erasmus contributing to the school’s curriculum, and the High Master receiving a weekly salary of 13s 6d double that of Eton, the school was off to a grand start.

Destroyed in the Great Fire of London, it was rebuilt twice more in the city centre, however as the population began moving to more outlying areas, it was decided the school should occupy new and larger premises in Hammersmith near the river. The move coincided with a renumbering of surrounding streets, and whether by accident or design, their address became 153 Hammersmith Road . . . just down the road from the Sly’s apartment.

From 1924 to 1934 the Slys lived in flat number 2 at 95 Hammersmith Bridge Road, on the corner of Ship Lane. The Old Ship, previously a pub, and not to be confused with the present-day Ship Inn further along the riverbank, had been converted into four self-contained flats (long since demolished for a housing complex and new access road to Hammersmith Bridge). Louis Roberto and Bertha Togni (pronounced Tony) lived in apartment 4. They were owners of a local ice and ice cream factory with ice wagons and billboards around town. At this time AEG was working for W. Cook, a builder and decorator on St. Andrews Road in Clacton, and as a sideline for extra income he created the advertising on ice wagons and billboards. Occasionally, when Kate was expecting Kathleen and Pauline, Mrs. Togni would take her a dish of ice cream as a treat.

Living briefly in one of the other flats were Kate’s parents (Frederick and Ellen Reynolds – presumably there had been a reconciliation), and just 5 houses along Hammersmith Road were Kate’s brother Will and wife Maggie (McArthur) at number 103.

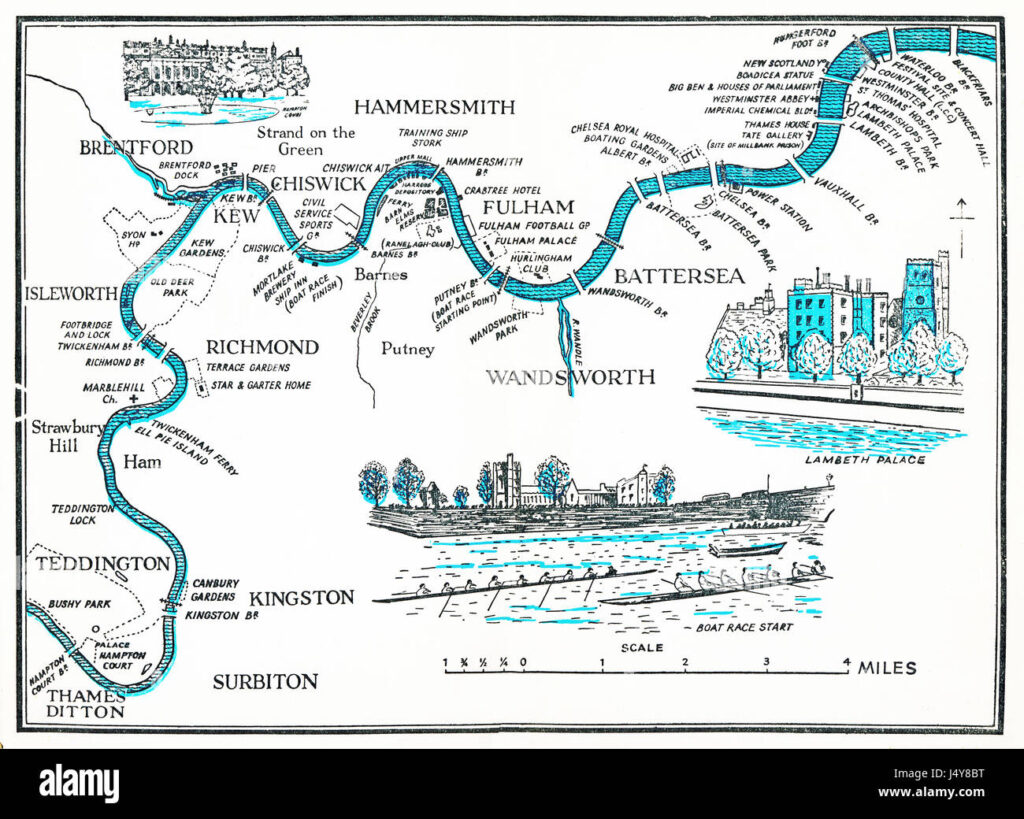

Hammersmith Bridge and the Thames were just steps away from home, and what a vibrant and kaleidoscopic thoroughfare that must have been. Pleasure steamers plying between Kew and Richmond in one direction, or down to Westminster and Greenwich in the other. Vast steam ships from far-flung exotic shores; grubby tramp ships transporting coke and coal to factories; heavily laden sailing barges carrying all manner of goods and essentials to the docks, warehouses, pubs and businesses lining the shore; hard-working tugs, like little terriers – worrying and nudging vessels into place or pulling lines of barges. Larger map here

Upstream from the port and docklands, where the river was less congested, rowing sculls skimmed across the surface like determined water beetles, blades dipping and glinting, coxes slouched and bellowing. Regattas abounded throughout the summer, and for some, culmination was the Boat Race between Oxford and Cambridge university eights – held annually since 1859 (excepting both world wars and Covid Pandemic in 2020). The S-shaped course of 4.2 miles (6.8kms) covers a distance between Putney and Chiswick Bridges with Hammersmith Bridge at just under the halfway point. It is rowed upstream with an incoming tide to give the fastest possible current, and a coin toss determines starting side. Depending on wind and weather, the Middlesex side gives rowers an advantage in the first and last curves, while the longer middle bend benefits the Surrey side. Then and now, huge crowds of spectators line the banks and bridges, some running or biking along the footpaths to keep pace – everyone sporting light blue for Cambridge or dark blue for Oxford. To date (2024) Cambridge has had 87 victories to Oxford’s 81 with one hotly contested dead heat and three sinkings apiece.*

An unconfirmed but lingering family rumour persists that Kate was acquainted with a person known only as Leonard. Had she become a little jaded with her current life … was he a chance encounter in the park? . . . or someone with whom AEG worked? – the details will forever be lost in the mists of time. He did, however, have A CAR – a rare luxury in those days. We know that on at least one occasion Leonard had arranged to take Kate and the girls, Kathleen and Pauline, out for an afternoon spin and on the day in question, as RG was returning to school after lunch he stopped by the local sweet shop to purchase a ‘surprise egg’. So engrossed was he in unwrapping the treat, he failed to notice a group of workmen gathered around a hole in the road ahead. Just as he walked by, one of the navvies swung back a pickaxe, completely knocking the young lad off his feet. No doubt winded and mildly concussed, though still clutching his treat, concerned neighbours found and escorted him back home. His mother was not best pleased at having their afternoon outing spoiled — RG, on the other hand was delighted … not only did he have his sweets, but a car ride as well.

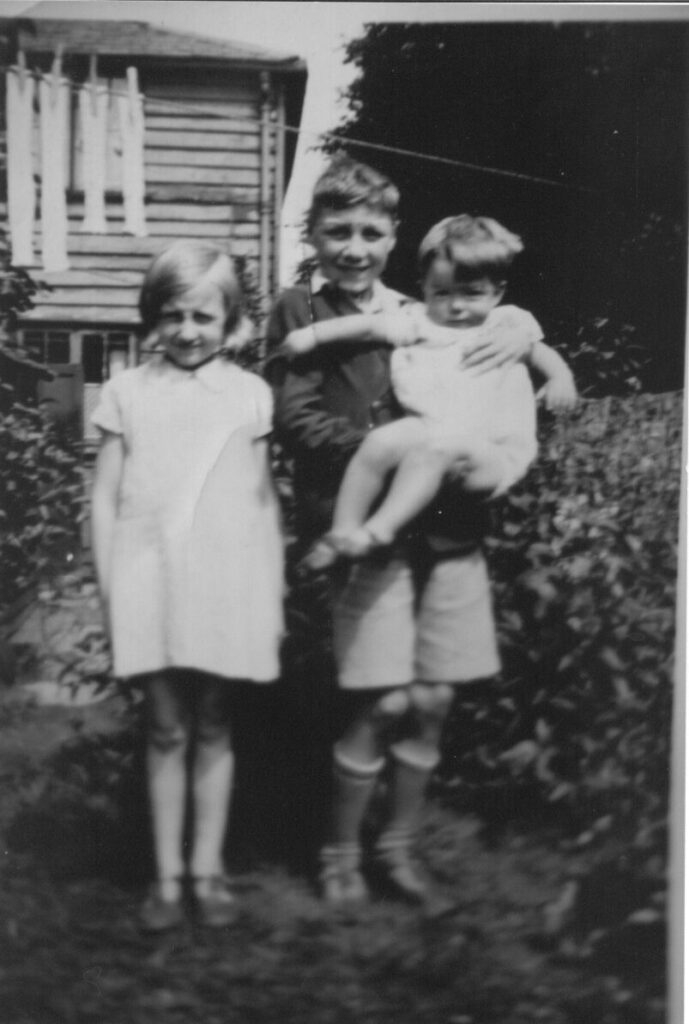

As a youngster with two sisters, four and eight years his junior, RG was given a remarkable amount of unsupervised freedom and, and come Saturday, a 6d all-day tram pass meant he had the huge, exciting city of London in his pocket. By end of day, the ticket would be punched so full of holes it resembled nothing more than lace. Many of the museums were free to enter … however RG shunned the dry, boring ones like Victoria & Albert in favour of the Science Museum with its working models, or the Imperial Institute showing travel or instructional films.

Cinemas were popular as colour films were gradually replacing black and white. RG and cousins Fred, Bill & Len (Reynolds) would, if possible, sneak in and sit at the back – often watching a film through a second time. Movies like The 39 Steps; The Scarlet Pimpernel; Of Human Bondage; The Man Who Knew Too Much … and stars such as Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Charles Laughton, Merle Oberon, Bette Davis, Leslie Howard and Peter Lorre.

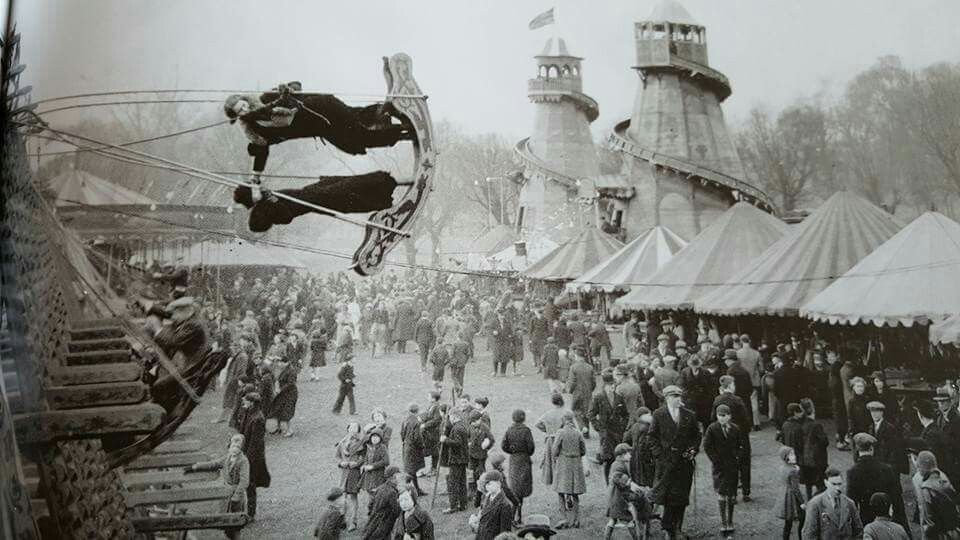

London was a wonderland of parks, pleasure gardens and common green spaces to explore. Vast Royal Parks like the ones at Richmond and Bushy which had herds of roaming deer; Hyde Park and Kensington contained boating lakes and lidos (swimming baths) plus a special pet cemetery in a corner of Hyde Park with touching and often amusing headstone inscriptions. Of course ‘Speakers’ Corner‘ is a well known free speech area where people often bring their own ‘soap boxes’ to stand on. Battersea and Hampstead Heath, on the other hand, were favourites for fairgrounds, and skating when the lakes froze over in winter.

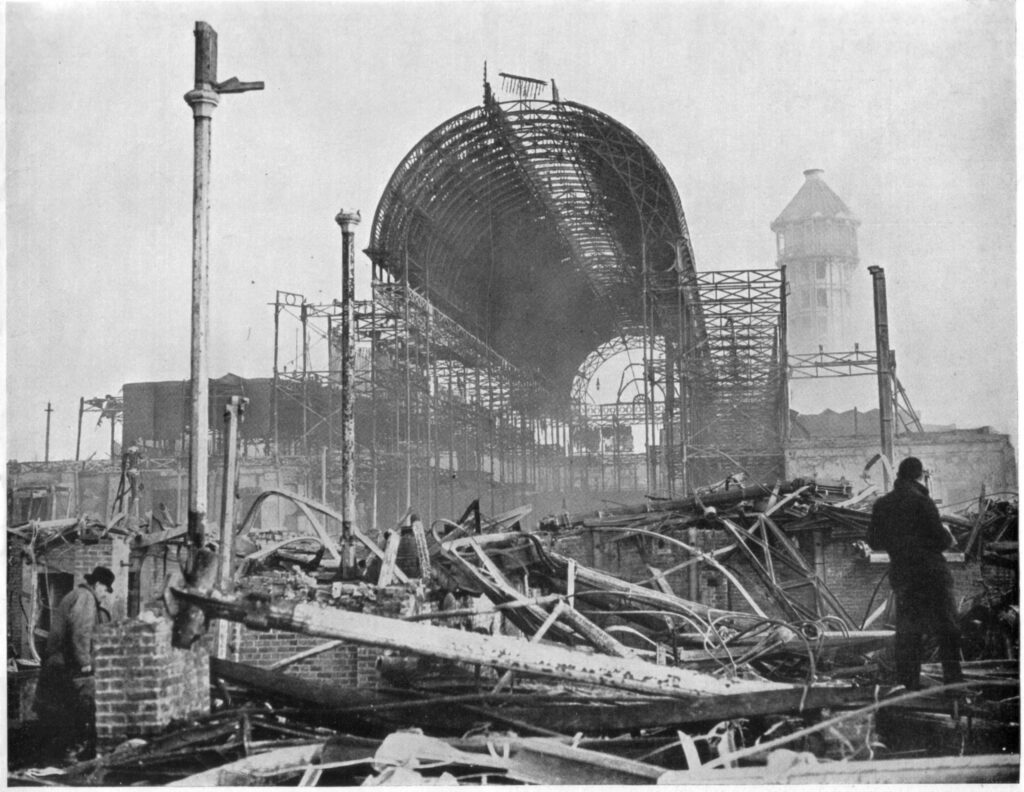

Crystal Palace, a gigantic glass and metal structure built in 1859 as an exposition to showcase British and Commonwealth goods, burnt to the ground in 1936 – the fire could be seen from all over London, and left rivers of molten glass and a blackened skeleton. At 16, RG remembered it well.

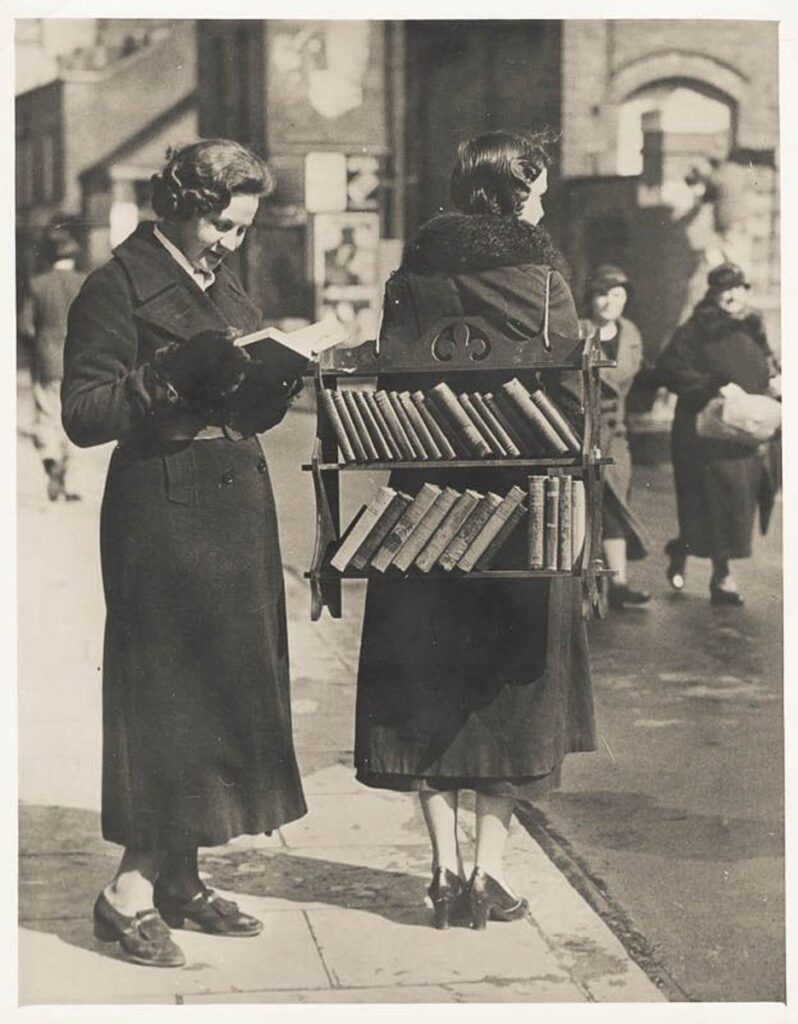

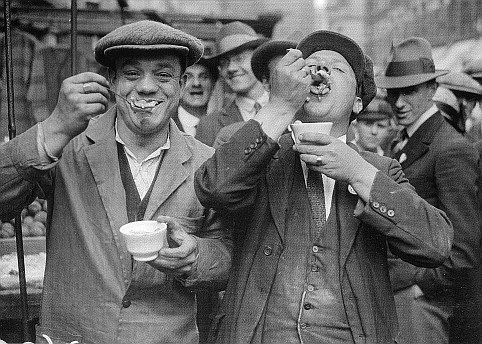

Street Markets were where most Londoners shopped – especially working-class families. Costermongers would have collected surplus meat, fish and produce from well-known wholesale markets .. places like Smithfield, Billingsgate, and Covent Garden to display on their carts and stalls to sell at bargain prices. You could buy almost anything – from clothes, household good, carpets – even a washing mangle if needed, however it was still a case of ‘buyer beware’ as quality could often be questionable. Banter between costermongers, barrow boys and customers was usually loud and cheeky … showmanship and sales patter fine-tuned, sometimes over generations, to attract no-nonsense housewives with tight purse strings.

Entertainment abounded in the form of sideshows, jugglers, acrobats, and novelty acts. Food stalls were plentiful – roasted chestnuts on coal braziers – popular on cold winter months, fresh cockles, mussels and whelks, buckets of jellied eels, bright red saveloys (spicy sausage), pie & mash drizzled with ‘green liquor’ (parsley sauce).

Saturday night was when markets were at their busiest and real bargains were to be had. Families with weekly wages jingling in their pockets would shop for Sunday dinner and the week ahead … sometimes waiting until the last minute as prices would drop as the evening progressed. As one trade unionist wrote: “About quarter to nine, people would be waiting for the perishable food to be auctioned off: women in black shawls surrounding the butcher in his striped apron, holding up the meat under kerosene lamps”.

For reasons unknown, RG was never encouraged by his parents to do well at school … in fact he resorted to hiding his text books inside comics in the event he was checked on. Despite this, RG excelled … and by age 10½ was already equal to the top percentage of 14 year-olds. However, as he prepared for the standard Eleven Plus exam, misfortune struck, and he contracted ‘Scarlatina’ (Scarlet Fever). He was initially isolated at Fulham hospital, before being shipped off to one of the ‘Fever Hospitals’ in Dartford. Originally built as Asylums for the rapidly expanding London populations, they were converted to Smallpox hospitals before vaccine made them more-or-less redundant. During the 1920s and 1930s outbreaks of Scarlet Fever and Diptheria meant that tens of thousands of children needed a place to convalesce – sometimes for several months — while still receiving some form of education. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2789011/

The food was pretty awful, and to while away the boredom, RG made up the following ditty:

There is a happy land far, far away

Where we get bread and jam three times a day

Eggs and bacon we don’t see

We just get brick dust in our tea.

And we are gradually fading away.

Unable to take the 11+ which would have the opportunity of moving on to grammar school (Latimer and Godolphin) he ended up attending West Kensington Central Secondary instead. One thing his parents did encourage him to pursue was music lessons … disappointingly not his preferred piano, but (in his opinion) a much lowlier instrument — the violin. His mates taunted him mercilessly, so he found a modicum of revenge in wielding the hefty oak case as a deterrent!

With the family now living at 7 Swinburne Road in Putney, a teenage RG — in possession of a bike — set his sights further afield, often cycling great distances into the surrounding countryside … even venturing as far as Brighton on several occasions – a distance of 58 miles … each way. There were Scouts and paper rounds, Saturday morning cinemas and come Autumn, conker contests.

Leaving school in the latter part of 1934 at age 14½, RG, briefly dabbled with being a door-to-door salesman for Kleeneeze. Similar in concept to Fuller Brush in the US, but developed in1923 Bristol by perhaps an aptly-named Harry Crook. Finding it tedious and not particularly productive, RG procured work in the sheet metal shop of Darracq Motor Engineering Company on Barlby Road, Ladbroke Grove, North Kensington, with the ambition of qualifying as a panel beater. This French company with a colourful, eclectic and somewhat tenuous financial background, made bodies for touring cars, charabancs, buses, taxis, equipment and vehicles for the war effort … and exotic racing cars. After moving production from Paris to London, they incorporated Sunbeam and Talbot cars under the collective name of STD Motors, however chronic financial mismanagement and ambitious expansion into racecar development led to its demise in 1936.

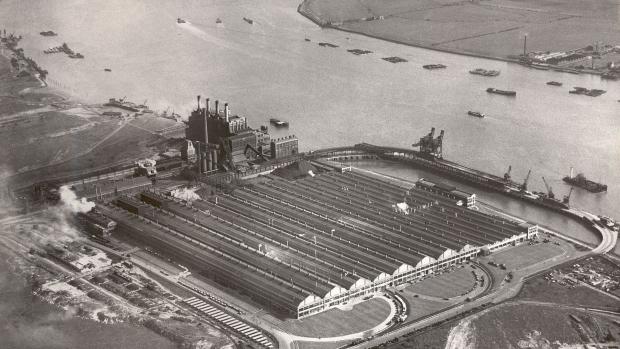

A position became available at Ford’s in Dagenham where RGs father (A.E.G. Sly) was already working. In 1931, the Ford Motor Company had relocated its plant from Trafford Park in Streatford to Dagenam, already the location of Briggs Motor Bodies – a US company manufacturing car bodies for Ford. It was a massive 500 acre river-side site destined to become Europe’s largest car plant (video) – complete with its own blast furnace and power station. Then in 1935, Riley signed with Briggs Bodies to mass produce steel bodies for their cars. RG apprenticed for 3 years as an engineer and would have qualified in another year had misfortune not intervened. It was a long commute … 22 miles each way. One morning as he was slip-streaming behind a large truck, the dynamo on his bike slid down and hit the rapidly spinning spokes of his front wheel, catapulting him over the handlebars and leaving him stranded in the middle of nowhere with a mangled bike and not a penny to his name. He left the bike at a house in exchange for bus fare, intending to go back and collect it later. He never did.

There were interim fill-in jobs, for example with a cabinetmaker near Delage’s that made wooden board games like bagatelle (the predecessor to pinball) https://youtu.be/agamnUk5Y84, and at an Aluminium Foundry – possibly with the name Klean Cast, in East Sheen making car number plates and road signs.

A German engineering firm on Barnes Common was certainly much closer to where he lived. It appears Health and safety was not a company priority, as there were several instances of worker injuries … including one to himself. While four workers were transporting a large sheet of metal. A workmate lost his grip – dropping one end of the panel onto RG’s finger, and even though it eventually healed, the nail always retained a split. Workers were never compensated, and shortly before World War II, the company closed shop and moved back to Germany.

By now, at age 17 R.G. felt perhaps a steady occupation with more scope might be beneficial and expressed a strong desire to join the Royal Navy. Still under age, he asked a friend’s father living across the street and who was already in the navy if he would sign his joining up papers. Mr. Terry readily agreed, providing R.G. showed them to his parents first. This didn’t go well … the papers were immediately torn up and the Terrys were never spoken of or to again.

Needing something to do until old enough to sign his own papers, RG found a position with an engineering firm and trained on a Capstan lathe: https://youtu.be/xCAE0pSUNvA. The owner felt RG showed great potential and was hugely disappointed when the following year, RG handed in his notice in order to enlist.

Having reached the age of 18 he no longer required parental consent and promptly signed onto the Royal Navy medical branch – mainly because their uniforms were much better looking than round hats and bellbottoms! His mother was furious and continued to create a fuss, claiming that as they had ‘kept’ him since birth, he should be reimbursing them. In order to keep the peace, he signed over 10 shillings a week from his paltry pay package … which during basic training was a tad over 14 shillings.